By Jane Blessing

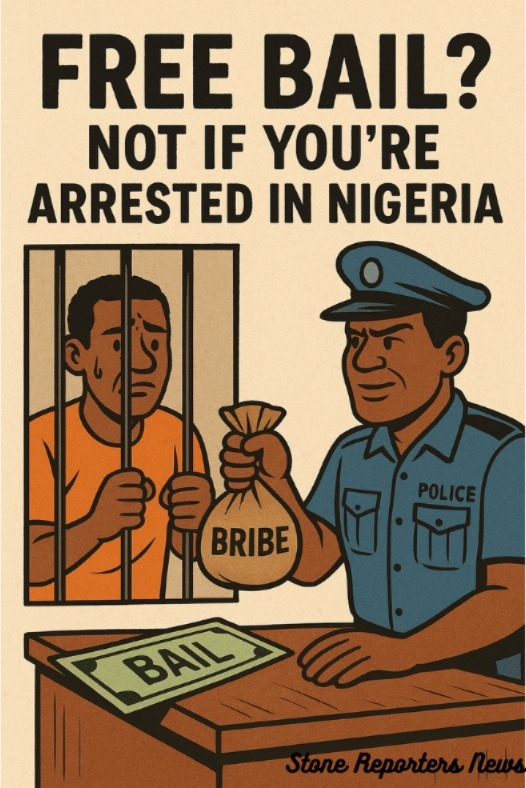

At almost every police station across Nigeria, a bold sign proclaims: “Bail Is Free.” For millions of Nigerians, however, that phrase is little more than an empty promise, a cruel irony that mocks the poverty of the people it claims to protect. Despite repeated reforms and the mandates of the Police Act of 2020 and the Administration of Criminal Justice Act of 2015, police extortion remains deeply embedded in the nation’s law enforcement culture. Surveys conducted by the CLEEN Foundation in 2023 found that over two-thirds of Nigerians who had contact with the police reported being asked for bribes, and Transparency International has consistently ranked the Nigeria Police Force among the country’s most corrupt public institutions. These figures are reflected in the countless personal testimonies of citizens who have been forced to pay for their release after minor offenses, including traffic violations and curfew infractions.

The roots of this practice are both complex and institutionalized. Retired officer ASP Jibril Danladi explained that extortion had already become normalized when he joined the force in the 1980s, with officers relying on informal settlements from the public to fund operational needs such as fuel, transportation, and feeding detainees. Chronic underfunding, poor salaries, and under-resourced stations have created an environment in which extortion is not simply tolerated but seen as necessary for survival. Dr. Uju Okafor, a criminologist at the University of Lagos, observes that corruption within the police is as much a structural problem as a moral failing, and it persists because it has been normalized at every level of the force.

The methods of extortion are subtle yet systematic. Police rarely demand bribes outright, preferring terms like “mobilization,” “fuel money,” or “paperwork fees,” implying that non-compliance will delay or nullify the release of detainees. During visits to stations in Lagos and Ogun States, Stone Reporters observed firsthand how suspects were informed that bail was technically free, but officers expected payment to process files promptly. The practice is often justified internally as a response to slow government funding and administrative constraints, reinforcing a culture in which citizens are coerced into paying for rights they are legally entitled to.

Even high-profile reform efforts have done little to alter this reality. The #EndSARS protests of 2020 briefly raised hopes that police brutality and extortion would be curtailed, but a 2024 report by Human Rights Watch confirmed that these practices remain widespread, particularly against the poor and marginalized. Citizens’ fear of reprisal and weak internal disciplinary mechanisms ensure that extortion continues largely unchecked. Oversight units like the Police Complaints Response Unit exist on paper but are largely inaccessible to the public.

The societal consequences are profound. Beyond financial loss, extortion erodes public trust in law enforcement, leaving citizens reluctant to report crimes and communities increasingly vulnerable. Investigations indicate that funds collected from detainees are often passed upward within the police hierarchy, creating a self-sustaining system that embeds corruption deeply into the institution’s operations. At the Makurdi Police Division, a young trader named Ifeanyi Eze held a small slip of paper documenting the payment he was forced to make before his brother’s release, describing his experience as a stark reminder that freedom in Nigeria often comes with a price.

The persistence of police extortion underscores the fragility of Nigeria’s justice system and the systemic inequality faced by citizens. Until structural reforms address salaries, accountability, and transparency, the promise of free bail will remain little more than words on a wall, a symbol of a law that exists in theory but is denied in practice.

📩 Stone Reporter News | 🌍 stonereportersnews.com

✉️ info@stonereportersnews.com| 📘 Facebook: Stone Reports |

🐦 X (Twitter): @StoneReportNew | 📸 Instagram: @stonereportersnews

Sister Sources: CLEEN Foundation (2023), Transparency International (2023), Human Rights Watch (2024), RULAAC (2023), Stone Reporters field interviews in Lagos, Ogun, and Makurdi (2025).

Add comment

Comments